For over 30 years, the U.S. government wasn’t sure exactly who Kelvin Johnson was.

The confusion dates back to 1988, when the disabled military veteran from the Bronx had his identity stolen by a mystery man. That triggered off a more than three-decade-long odyssey for Johnson to prove his identity.

While his case is among the more extreme, it’s not unheard of, officials say. Uncoordinated databases among government agencies in the 1980s and 1990s made it far easier for people to assume someone’s identity and keep it. Improved communication between agencies these days has led to the discovery of a surprising number of cases of people whose names were stolen decades ago.

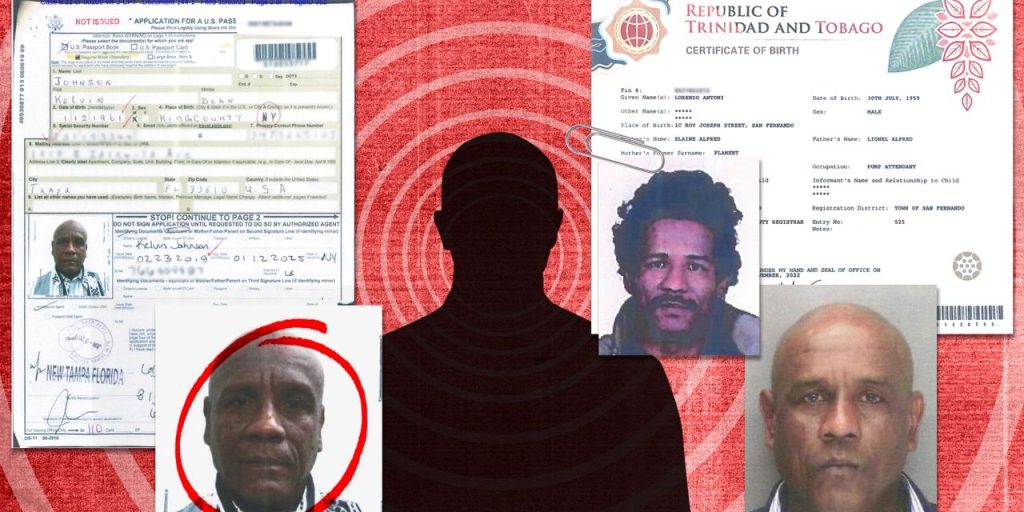

For Johnson, it took until 2019 — when the fake Kelvin Johnson submitted an application in Florida for a passport — for authorities to determine that there were two people claiming to be the same man.

Lorenzo Antoni Alfred first assumed Johnson’s identity in New York in 1988, federal investigators said, but it would take them decades to learn the imposter’s real name. Within a year of stealing Kelvin Johnson’s identity, Alfred committed a murder — gunning down a bartender on his way home from work during a robbery-gone-wrong in Greenwich Village, court documents show. The identity-thief killer then spent the next 25 years in prison as Calvin Johnson, a variant spelling of his assumed name, court records show.

The real trouble for the actual Kelvin Johnson began when the imposter was released from prison in 2014 and the imposter began receiving government benefits in Johnson’s name, investigators said.

Soon after, the real Johnson found himself being repeatedly rejected for his military disability and social security benefits, and the food stamps he was eligible to receive. His credit score dropped below 600 and he had credit card applications rejected 10 times, according to court records. In 2015 and 2016, he had to file identity theft affidavits to the Internal Revenue Serivce to avoid paying taxes the imposter actually owed.

“He was faced with this bureaucratic nightmare of having to explain that he is the real Kelvin Johnson, over and over again,” said Sean Berk, a special agent with the Diplomatic Security Service of the Department of State, who finally cracked the case. “He’s a disabled veteran just trying to get by — it was a lot for him to deal with.”

A common long con

Berk said while it is not unheard of for a person to use a stolen identity for decades, what made Johnson’s case stand out was that two living people used the same name for so long.

“What we typically see is someone assuming the identity of someone who died, usually a long time ago. If it was, say, an infant who died in the 1940s in Nebraska, it was far easier for an imposter to get away with that, sometimes indefinitely,” he said.

Officials point to other examples of long-term identity theft:

- In 2017, Cynthia Lynn Knox was sentenced to three years in prison for stealing the identity of a dead infant in 1988 after police in California opened a probe into the mysterious death of her husband. Knox spent the intervening years as the captain of a dinner theater cruise ship in Texas before getting caught renewing her pilot’s license.

- In 2020, Howard Farley Jr., was given a four-year sentence after living for over 35 years under the name of a deceased three-month-old baby while on the run from charges that he ran a sprawling drug distribution empire from Nebraska.

- Doitchin Kratsev served two years in prison for stealing the identity of a 3-year-old boy murdered in a kidnapping in 1982. Kratsev, an exchange student from Bulgaria lived for around 15 years as Jason Evers, even getting a job as an investigator for the Oregon Liquor Control Commission.

Two lives intertwined

In each instance where Kelvin Johnson encountered difficulties, he was ultimately able to get his benefits back, but the case caught the attention of officials at the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Social Security Administration, Berk said. While they were able to restore Johnson’s benefits, they were unable to definitively pin down what the fake Kelvin Johnson was up to exactly.

Berk says the ex-con had settled in Brooklyn, just 10 miles from where the real Johnson lived, and got by working for the Doe Fund, a non-profit that helps the formerly incarcerated get started again once freed. He also did odd jobs around his neighborhood for some extra cash.

But in 2019, he briefly relocated to Tampa, where he filed a request for a passport for a planned trip to the United Kingdom, complete with a copy of the real Kelvin Johnson’s birth certificate. When cross-referenced against other government databases, the file was quickly flagged and rejected, court documents showed.

That’s when the case was given over to Berk to investigate. He said it was clear that it was a case of identity theft but the first thing he needed to do was to determine which of the Kelvin Johnson’s was the real one.

The answer came quickly. Berk said that when Veterans Affairs had looked at the case, they had spoken to the phony Johnson and that his answers made no sense.

“I’m a veteran and I could tell immediately this guy was making it up. He said he couldn’t remember where he did his basic training and claimed he had served in Afghanistan,” Berk said. “First off, no one forgets where they did their basic training and we were talking about the 1980s here, so unless this guy was in the Mujahedeen, that wasn’t really possible.”

That gave federal prosecutors in Florida enough to file fraud charges against the imposter and arrest him, but they still had a problem: they had no idea who the phony Kelvin Johnson they had arrested actually was. Even at this point, he continued to insist that he was Kelvin Johnson, so the case was filed against John Doe.

The mystery behind the mystery man

The identity thief had a very strong West Indian accent, so as the case made its way through court, prosecutors brought in a linguistics expert who specialized in creole dialects to try to figure out where the man was from. The expert determined from the man’s accent that while he had spent considerable time in the New York area, he likely came from somewhere in the southern West Indies, like Barbados or Grenada.

Eventually, Berk zeroed in on a clue — on the passport application, the identity thief had included the name and number of an emergency contact in Florida. Berk called the person, who turned out to be an actual relative of the imposter and solved the mystery.

Berk learned that he phony Kelvin Johnson was actually named Lorenzo Antoni Alfred. He had actually been born in Trinidad in 1959, but had left for New York in 1988 to flee a drug charge in his home country, prosecutors said. Given that fact, Alfred should have been deported after serving time for murder, but was allowed to remain because authorities believed he was a U.S. citizen due to the identity theft.

Alfred suffers from mental illness and his attorney argued in court filings that his client’s understanding of his own identity was shaky. In interviews with court-appointed psychiatrists, Alfred said he had little recollection of his childhood and couldn’t remember where he was from. He believed he had been adopted. He had little to no education, according to court papers.

His attorney didn’t respond to messages seeking comment.

In May, Alfred pleaded guilty to one count of aggravated identity theft. Earlier this month, he was sentenced to seven years in prison. “Even at the end, he still did not admit he was Tony Alfred,” Berk said.

Despite all the financial difficulties Kelvin Johnson experienced as a result of the case, the thing that bothered him the most was the fact that Alfred had claimed his military experience and had named Johnson’s mother as his own in paperwork he had filed throughout the years, Berk said. Attempts to reach Kelvin Johnson were unsuccessful.

“That really left him feeling the most violated,” Berk said. “It was very upsetting to him.”

Read the full article here