Progress at COP28 on structuring carbon (dioxide) offset markets will be in the right direction; but there is a serious risk of the resulting prices being too low and jeopardizing the future health of the planet.

The global market for carbon offsets falls under Article 6.4 of the Paris climate agreement. A study jointly conducted by the International Emissions Trading Association and the Center for Global Sustainability at the University of Maryland provides price forecasts for this market. The inflation adjusted forecasted market price per metric ton of carbon dioxide for the year 2030 is $27, and for 2050 is $175.1 In order that these prices be effective at keeping the global temperature increase below 2°C,, they need to be close to their respective social costs of carbon. Numbers are important here, and unfortunately, $27 and $175 are simply too low to do the job effectively.

Context

The context for Article 6.4 is the set of carbon emission pledges, called nationally defined contributions or NDCs, which countries made at COP21 in Paris. Some countries find it more expensive than others to reduce their carbon emissions. A carbon offset market allows the more expensive countries to pay the cheaper countries to do the job for them.

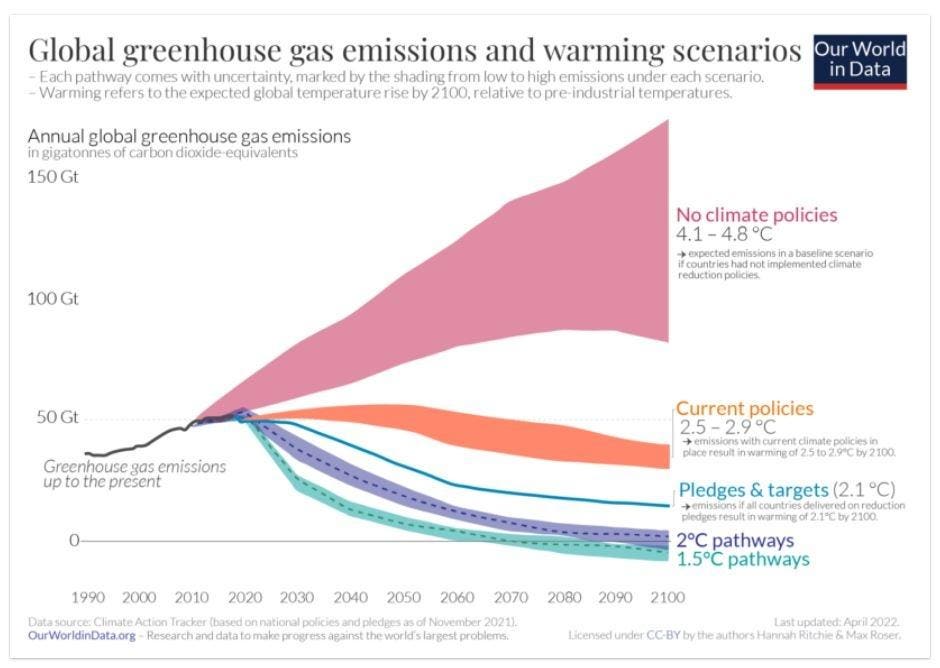

Consider the following figure, which displays alternative greenhouse gas scenarios, as if all emissions were carbon dioxide. The top pink set of scenarios illustrate plausible emission pathways if the world were to continue to follow business as usual behavior, as it has done throughout the industrial age. The orange group pertains to current policies. Below the current policies is a thin region of pledges & targets scenarios associated with the NDCs. Below the NDC scenarios are two aspirational groups, one pertaining to the achievement of 2°C and the other to 1.5°C. Notice that the bottom three scenario groups feature net zero emissions being achieved around mid-century.

To the right of each scenario group you will see the estimated associated end-of-century global temperature increases. For no climate policies, the temperature change rises above 4°C. For current policies, it is between 2.5°C and 3°C. For the pledge-based policy it is 2.1°C.

Conceptual Valuation Questions

The emission scenarios and associated consequences represent choices. The global community needs to explicit attention to the issues of valuation and sacrifice in respect to these choices. The evidence suggests it has not.

Consider an analogy between climate policy choice and the choice of leasing an apartment. One apartment option is to squat in an abandoned building, live unsafely, but pay no rent. That is akin to following a No Climate Policy scenario, for which I use upper case notation for ease of identification. A second option is to choose low rent substandard housing, which is somewhat uncomfortable but not as dangerous as squatting. This is akin to following a a Current Policy scenario. Choosing higher quality apartments entails higher rental payments, akin to a higher quality climate with lower global temperatures. Think of the bottom three scenarios in the figure as choices with successive higher quality.

With the analogy in mind, consider the following question. Ballpark, what percentage of your standard of living would you be willing to sacrifice, maximally per year, to lease the planet from now until 2050 so that global temperatures fall between 2.5°C and 3°C instead of being above 4°C? For example, if your total consumption of goods and services per year were $100,000, how much of that would you be willing to sacrifice, maximally, to live on a 2.5°C-to-3°C planet instead of an above 4°C planet?

Please give a moment’s thought to answering this valuation question and the ones below. You will get more from continuing to read this post if you do.

Now ask the same question for the Pledges & Targets scenario. If your total consumption of goods and services per year were $100,000, how much of that would you be willing to sacrifice, maximally per year from now until 2050, to live on a 2.1°C planet instead of on an above 4°C planet? Repeat the question, but for the 2°C scenarios and then the 1.5°C scenarios.

There will be a spectrum of readers’ responses to the questions. Collectively, these responses identify the global community’s willingness to pay for different levels of emissions control. This is important because such valuations will be reflected in the market prices for carbon offsets.

These valuation questions are significant. As a community in dialogue we need to ask them explicitly, but refrain from doing so. The issue is important because by avoiding these questions, we risk ending up leasing a lower quality planet than a higher quality one we would be willing to pay for.

Economic models produce estimates about the kinds of sacrifice required per capita, to reach each set of scenarios. For No Climate Policies, it is of course $0 per $100,000 of consumption. For Current Policies, it is between $100 to $200, starting at $100 in 2025 and rising over time to $200. For scenarios relating to Pledges & Targets, and to 2°C, it is between $2,500 and $5,000 starting at $2,500 in 2025 and rising until the point when net zero emissions are achieved. For 1.5°C, a lot depends on how quickly the global economy can move to net zero emissions, and whether it will be possible to achieve net negative emissions before 2045. The state of technological progress around alternative energy and greenhouse gas removal will be central issues here. A rough valuation estimate range for achieving 1.5°C is $18,000 to $77,000, starting at $18,000 in 2025 and rising to the top end of the range by mid-century.

The analysis used to produce the above economic estimates features an implicit assumption, namely that the global economy is efficient at reducing emissions.

In the end, which scenario the global community follows will depend in large part on how much the community is willing to pay. A lower quality planet with higher temperatures is certainly cheaper; but, so is squatting.

Social Cost of Carbon

While the social cost of carbon is less intuitive than a market price, it is straightforward to describe. Pick one of the scenarios, and focus on a point in time. For example, pick the top scenario in the Current Policy group, and focus on 2030. Suppose the social cost of carbon were to be $50 per ton for Current Policies. That would mean that the value of the damage done to global gross domestic product, post 2030, from emitting one more ton of carbon in 2030 is $50.

Implicit in this last statement is the assumption that the global economy is efficient at reducing emissions. If the economy is inefficient, then the associated damage will be more than $50.

By way of contrast, were we to pick the top scenario in the Pledges & Targets group, the social cost of carbon for 2030 might be $290. Indeed, economic studies indicate that both $50 and $290 are plausible estimates.

There are benefits from burning fossil fuels, which is why we burn fossil fuels, despite the negative side effects. If the global community decides it wants to follow the Pledges scenario, then in 2030 it needs to price carbon at $290 a ton. This means that emitters choose to emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and will do so as long as the dollar benefit from doing so is at least $290 a ton. If the dollar benefits are, say $280 a ton, then increasing emissions is unprofitable.

Forecasted Market Price Of Carbon Is Low

My newly published book applying behavioral economics to global warming explains why carbon is being underpriced. In this regard, a key feature of behavioral economics is its focus on psychological phenomena that interfere with rational decision making.

As I mentioned above, the inflation adjusted forecasted market price for the year 2030 is $27 per metric ton, and for 2050 is $175. The 2030 value is closest to the estimated social cost of carbon corresponding to Current Policies than to the scenarios associated with Pledges & Targets, 2°C and 1.5°C. If the global economy is efficient in the way it deals with emissions, this means that emissions will lead the global temperature to rise be closer to 3°C than 2°C, let alone 1.5°C.

Remember: if the market price of carbon is low, then it will be profitable to emit more carbon into the atmosphere than when the market price of carbon is high.

For 2050, the forecasted market price of carbon, $175, is only 60 percent of the value associated with Pledges & Targets. However, it is higher than the social cost of carbon associated with Current Policies, which is about $90.

Carbon Taxes

Most mainstream economists recommend the use of carbon taxes, where carbon is taxed at its social cost. A carbon tax gets passed along to consumers, who pay more for goods and services that are carbon intensive. A carbon tax increases gasoline prices, electricity bills, and the prices of airline tickets. Higher prices induce consumers to shift their spending pattern from higher carbon products and services to lower carbon products and services. This means smaller vehicles, fewer trips in electric vehicles, less air conditioning, and less air travel.

The world needs a global carbon tax. But it does not have one, and most countries are reluctant to impose one. It is as if people are addicted to SUVs, air conditioning, and air travel.

Anna Lembke writes about addiction in her best seller Dopamine Nation, a book worth reading. Addiction is real and widespread. Dozens of U.S. states are suing Meta, claiming its products are addictive and harmful.

Opponents of a carbon tax emphasize the benefits of fossil fuels but ignore the costs, a feature consistent with addiction. A good example are tweets by anti-tax advocate Grover Norquist, who characterizes a tax on carbon as “a tax on the very thing that brought us out of the Dark Ages and ended 1000 years of stagnation.” Perhaps so, but this perspective ignores the climate threat facing the planet in the next 50 years, let alone the next 1000 years.

Norquist’s message reinforces addictive predispositions in his main audience, Republicans on the right end of the political spectrum. Addiction can also be reinforced with denial. In this respect, the new speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Mike Johnson, contends that the burning of fossil fuels is not adversely impacting the Earth’s climate. Johnson is from Louisiana, a major energy producing state. In my book, I discuss the psychological elements underlying denial, such as motivated reasoning and cognitive dissonance.

It is easy to focus on Norquist and Johnson as individuals. But keep in mind that they represent the views and attitudes of many millions of Americans

Not having a global carbon tax in place does not mean that we cannot achieve the carbon scenario we seek. It just means that achieving those scenarios will be a lot costlier than necessary, plausibly by a factor of five to seven. Incurring unnecessary costs is not rational, but we do not live in a rational world. Indeed, if the global community used carbon taxes to price carbon at its social cost, we would not need carbon offset markets.

Since the early 1990s, U.S. lawmakers have consistently rejected imposing a carbon tax. Nevertheless, another effort is underway. Citizens’ Climate Lobby is supporting passage of legislation called the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act. This Act would tax carbon at its source and distribute the revenues to the general population as a “dividend.”

Addiction and Pricing Carbon Below Its Social Cost

A recent study by the IMF highlights the degree to which carbon dioxide emissions are globally mispriced. The study states that if mispricing were totally the result of external subsidies, the value of those subsidies would be $7 trillion. Significantly, the value of the actual external subsidies is $1.25 trillion, 20 percent of the total.

As of 2021, the price of carbon was $19 per ton, and the value of the explicit subsidy was $11. Therefore, $11, corresponding to 20 percent, translates into a total subsidy of $55. This would make the social cost of carbon equal to $74, the sum of $19 and $55. The IMF has used $75 in the past as its estimate of the social cost of carbon.

Simply eliminating external subsidies would remove a substantial portion of the underpricing of carbon. Yet, the IMF notes that the problem has been getting worse, not better. Since 2020 explicit subsidies have doubled.

In a very real sense, the global population appears to be addicted to fossil fuels. The twentieth century economist Irving Fisher used problem drinking as an analogy to describe general addiction issues. I think it is a good analogy.

Problem drinkers often resist rehabilitation. Pop singer Amy Winehouse had a hit song “Rehab,” with the lyric “No rehab” making the point about resistance. She lived her name but also died her name, passing away prematurely of alcohol poisoning at age 27.

Problem drinkers who resist rehab also resist higher taxes on alcoholic beverages. Likewise, a global population addicted to fossil fuels resists efforts to increase the price of those fuels, and favors subsidizing the products to which they are addicted.

Taking the global price of carbon to be $19 a ton, if all fossil fuel subsidies were to be removed, the global price of carbon would rise to about $30 a ton. Notice that $30 today is higher than $27 in 2030, the forecast price on the global carbon offsets market. This difference is a manifestation of no rehab.

Take another look at the scenario chart depicted above. Why do you think the scenarios in the Current Policies group lie above those in Pledges & Targets? Think about resistance to rehab. Think about lack of self-control. In this regard, the $27 and $175 carbon prices were derived under the assumption that countries will honor their NDCs. If countries fail to do so, even $27 and $175 might be overly optimistic forecasts. This will make greenhouse gas removal technologies that much more important for reaching a desirable climate scenario.

COP28 will make serious progress on a framework to trade carbon offsets and to price carbon. Significantly, Article 6.4 covers offsets relating to greenhouse gas removal.

All of this will be a step in the right direction, just as a problem drinker takes a step in the right direction by joining Alcoholics Anonymous. However, just joining AA by itself will not address the addiction. Indeed, the first step in a 12-step program is overcoming denial and being honest about being addicted. The global community would do well to try it, in respect to being addicted to fossil fuel-intensive products.

Continuing to price carbon below its social cost will hinder the global community’s effort to deal efficiently with fossil fuel addiction. Let us hope it can find a way, most likely through greenhouse gas removal, to avoid Amy Winehouse’s fate.

Read the full article here